The American Marten in Michigan's Upper Peninsula: A History of Ecological Struggle and Enduring Cultural Significance

Overview

The American Marten (Martes americana), also known as the pine marten, holds a unique and complex position in the ecological and cultural history of Michigan's Upper Peninsula. Once a widespread native species across Michigan, the marten faced near extirpation by the 1930s, primarily due to extensive logging that destroyed its specialized habitat and unregulated trapping. Decades of dedicated reintroduction efforts by state and federal agencies have led to its re-establishment in prime U.P. habitats, though populations remain genetically vulnerable and face new threats from climate change. Beyond its ecological narrative, the American Marten is deeply woven into the cultural fabric of the region's indigenous Anishinaabe peoples, particularly the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi. As the revered Waabizheshi (Marten) clan totem, it symbolizes bravery, hunting prowess, and plays an integral role in their traditional social structures and oral traditions, underscoring the profound interconnectedness of species health and cultural continuity.

1. Introduction: The American Marten in Michigan's Upper Peninsula

1.1 Brief Biological Overview of the American Marten (Martes americana)

The American marten, often referred to as the pine marten, is a small, elusive member of the Mustelidae family, which includes weasels. These animals typically weigh around 2 pounds and possess long, slender bodies, measuring approximately 18-22 inches in length and standing about 6 inches high. Their fur coloration can vary from a pale buff to a dark brown, complemented by distinct black legs and long, bushy black tails.1 While adept climbers and capable of moving with remarkable ease through trees, martens primarily conduct their hunting activities on the ground, particularly during the crepuscular hours of dusk and dawn when their prey is most active.1

As omnivores, martens consume both plant and animal matter, though their diet predominantly consists of small rodents.1 A notable adaptation of the marten is its ability to thrive in snowy environments. Their "snowshoe-like paws" allow them to traverse deep, fluffy snow with relative ease, and they can also navigate beneath the snowpack (the subnivean zone) for protection or in pursuit of prey.1 This adaptation provides a significant competitive advantage over larger mustelids, such as the fisher, in areas with substantial snowfall.1 Unlike many other northern mammals, martens do not hibernate and remain active throughout the winter months, a characteristic supported by their high metabolism which necessitates a consistent intake of food for energy.1

The preferred habitat for American martens is characterized by structurally complex, mature forests. These environments often include extensive stands of large conifers like hemlock, white pine, lodgepole pine, Douglas fir, and spruce, frequently mixed with hardwoods.2 Martens favor forests with high canopy cover, typically ranging from 30% to 70%, and an abundance of coarse woody debris on the forest floor. They establish their dens in various sheltered locations, including hollow trees, rock crevices, or abandoned ground burrows.2 This specific set of habitat requirements means the marten is a habitat specialist 5, thriving in particular conditions. When these conditions are rapidly altered, for instance, through widespread logging, the species is disproportionately affected because it cannot easily adapt to or survive in fragmented or open landscapes. This inherent ecological specificity, while advantageous in stable environments, becomes a critical vulnerability when faced with large-scale human-induced disturbances.

1.2 Geographic and Ecological Context of Michigan's Upper Peninsula (U.P.)

Michigan's Upper Peninsula is a region historically defined by its rich, dense forests and diverse wildlife, which once provided ideal habitat for species like the American Marten.2 The human history of the U.P. is deeply intertwined with its natural landscape, beginning with the arrival of Algonquian-speaking tribes around 800 C.E. These indigenous groups, including the Ojibwe, Menominee, Odawa, Nocquet, and Potawatomi, primarily sustained themselves through fishing and other traditional practices.6

European contact commenced around 1620 with French explorers such as Étienne Brûlé, who sought routes to the Far East. This early engagement led to the establishment of fur trading posts and missions, notably at Sault Ste. Marie and St. Ignace, which became centers of interaction and commerce.6 Following the French and Indian War in 1763, control of the territory shifted to Great Britain, and then nominally to the United States in 1783, though British influence persisted until 1797 under the Jay Treaty.6 The fur trade continued to dominate the U.P.'s economy under American control, with entities like John Jacob Astor's American Fur Company playing a significant role. However, the industry began a steep decline in the 1830s due to the widespread overhunting of beaver and other furbearers.6 This pattern of early colonial economic activities, driven by resource extraction, not only depleted specific animal populations but fundamentally altered the ecosystems upon which they relied. This ecological disruption had ripple effects, impacting not only the marten but also the traditional lifeways and resource availability for indigenous communities, foreshadowing later, more severe ecological collapses.

1.3 Purpose and Structure of the Report

This report aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the American Marten's historical presence, its unfortunate extirpation, the extensive efforts undertaken for its reintroduction, and its current ecological status in Michigan's Upper Peninsula. Concurrently, it explores the profound cultural significance of the American Marten within the oral traditions and clan systems of the region's indigenous tribal communities.

2. Historical Presence and Extirpation

2.1 Native Range and Abundance in Michigan

The American marten is indigenous to Michigan, and historical records indicate its presence across both the Upper and Lower Peninsulas.2 Its historical distribution extended remarkably far south into the Lower Peninsula, with evidence of their presence in areas as southern as Allegan County.3 Similarly, in neighboring Wisconsin, a state with comparable ecological characteristics to the U.P., the marten's historical range encompassed nearly all of its forested areas.1 This widespread historical distribution suggests that martens were once a common and integral component of Michigan's forest ecosystems.

2.2 Primary Causes of Decline: Extensive Logging and Unregulated Trapping

The precipitous decline and eventual regional extirpation of American martens were primarily driven by two interrelated human activities: extensive logging of old-growth forests and unregulated harvesting by trappers.1 The late 1800s witnessed large-scale forest cutting and widespread overhunting across the region.8 Specifically, the "clear cutting of northern Wisconsin's coniferous and deciduous forests in the late 1850s-1930s, followed by searing fires," resulted in catastrophic habitat destruction that mirrored the situation in Michigan's U.P..1

The marten, being a habitat specialist requiring mature conifer components, significant canopy closure, and abundant coarse woody debris 5, was particularly vulnerable to these changes. Both large-scale habitat fragmentation, caused by land settlement and logging practices, and smaller-scale fragmentation severely impacted marten populations.5 While a trapping season for martens was reportedly closed in Michigan in the 1920s, this measure proved to be "apparently too late" to prevent the species' disappearance, as the cumulative impact of habitat loss and prior unregulated harvesting had already pushed populations beyond a critical threshold.3 This situation highlights a critical challenge in conservation: policy changes often lag behind the rate of environmental degradation and species decline. The legislative action, while well-intentioned, could not reverse the cumulative impact of decades of unsustainable practices, indicating a threshold beyond which recovery becomes immensely difficult without direct intervention.

2.3 The Period of Extirpation (1930s) and Identification of Remnant Populations

By the 1930s, the American marten was largely considered "extirpated," or locally extinct, from Michigan.1 Records from the Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR) confirm their elimination around this period.2 The severity of the decline was starkly articulated in a 1927-28 Biennial Report, which concluded that martens were "so nearly exterminated in Michigan that there appears no chance they will ever come back".2 This assessment reflected the perceived permanence of the extirpation at the time.

A small remnant population of martens did manage to persist in the remote Huron Mountains of the U.P., though the last observation in this area was recorded in 1939.3 In the Lower Peninsula, the last confirmed sighting occurred much earlier, in 1911, near Lewiston.3 The geographic isolation of Michigan's Upper Peninsula further exacerbated the extirpation, as it reduced the likelihood of a "rescue effect"—natural recolonization from nearby healthy populations. This was particularly true because concurrent habitat destruction and fragmentation were also occurring in Wisconsin, the most immediate potential source of new individuals.5 The pessimistic assessment in the 1927-28 Biennial Report, stating "no chance they will ever come back," reflected the perceived permanence of the extirpation. However, subsequent reintroduction efforts contradict this. This demonstrates that the ecological "debt" incurred by past generations through over-exploitation and habitat destruction is not necessarily permanent, but its remediation requires massive, sustained, and often costly intervention from future generations. It underscores the long-term consequences of short-sighted resource management and the significant effort required to restore ecological balance.

3. Reintroduction and Recovery Efforts

3.1 Early Conservation Initiatives and First Reintroductions (1950s-1970s)

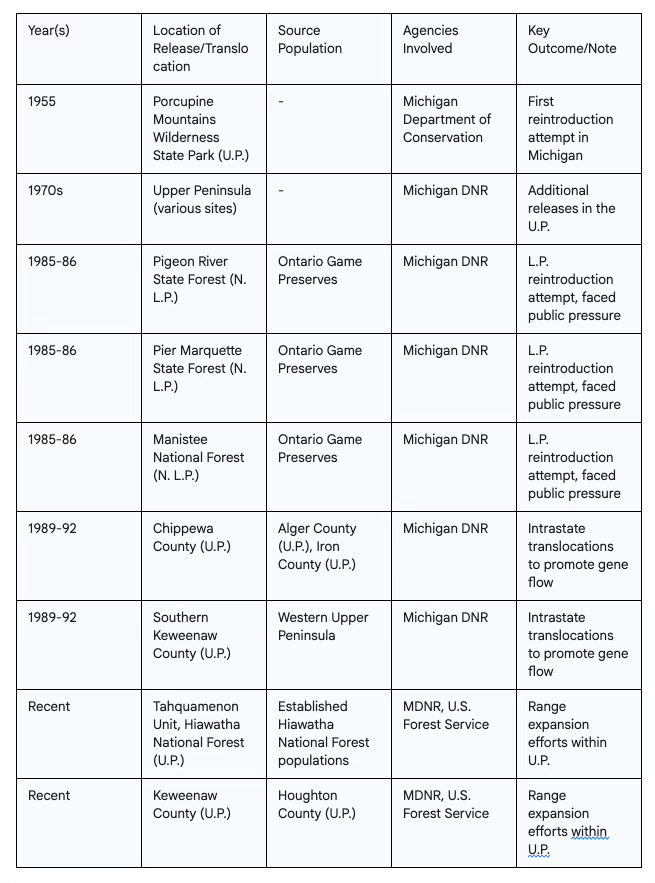

The dire status of the American marten prompted early conservation efforts aimed at re-establishing the species. In Wisconsin, reintroduction initiatives began as early as 1953 with the release of five martens on Lake Superior's Stockton Island.1 Michigan's own efforts commenced in 1955, spearheaded by the Michigan Department of Conservation.3 The initial reintroductions in Michigan took place in the Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park within the Upper Peninsula.2 This location was strategically chosen due to its exemplary marten habitat, characterized by mature hemlock stands and extensive areas of large conifers intermixed with hardwoods.3 Subsequent releases in the U.P. continued into the 1970s.2

An earlier attempt to reintroduce martens to the Apostle Islands, an archipelago near the U.P. in Lake Superior, occurred in the 1950s. This effort involved the introduction of ten Pacific martens sourced from Montana and British Columbia. However, this particular reintroduction proved unsuccessful, with the last marten detected on the islands in 1969.9

3.2 Major Reintroduction Programs and Intrastate Translocations (1980s-Present)

Reintroduction programs gained further momentum in the 1980s. In 1985 and 1986, martens were transferred from Ontario Game Preserves to several locations in Michigan's northern Lower Peninsula, including the Pigeon River State Forest, Pier Marquette State Forest, and the Manistee National Forest.3 The Michigan DNR had initially hoped to relocate a significantly larger number of martens (around 200) to viable habitats in the Northern Lower Peninsula. However, these plans were curtailed due to public pressure and criticism directed at the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources for the removal of such a large number of animals from their established populations.3

More recent efforts to expand the marten's range have focused on the U.P. These initiatives involved cooperative endeavors between the MDNR and the U.S. Forest Service, relocating martens from well-established populations within the Hiawatha National Forest to its Tahquamenon Unit, and from Houghton County to Keweenaw County.3 To further bolster populations and address genetic isolation, a series of intrastate translocations were conducted within the U.P. between 1989 and 1992. During this period, 20 martens were moved from Alger County to Chippewa County, 27 from Iron County to Chippewa County, and 19 from the western Upper Peninsula to southern Keweenaw County.5 These multiple reintroductions and intrastate translocations were strategically undertaken to counteract the detrimental effects of small population sizes, habitat fragmentation, and geographic isolation by facilitating gene flow and promoting genetic exchange.5

The numerous reintroduction and translocation efforts across different parts of Michigan, including attempts to facilitate genetic exchange and the observed natural dispersal between the U.P. and Apostle Islands, underscore that marten conservation cannot be limited to isolated pockets. The challenges of habitat fragmentation and genetic isolation necessitate a landscape-scale approach that considers connectivity, genetic exchange, and the establishment of robust meta-populations rather than just individual reintroduction sites. This implies that future management must prioritize maintaining and creating corridors for movement and genetic flow across broader geographic areas.

Table 1: Key American Marten Reintroduction Efforts in Michigan's Upper Peninsula (1955-Present)

3.3 Challenges to Re-establishment: Habitat Fragmentation, Genetic Bottlenecks, and Public Pressure

Despite extensive efforts, the re-establishment of American marten populations has faced significant challenges. Reintroduced populations are inherently smaller and more isolated than native populations, leading to a rapid loss of genetic variation.5 Studies on reintroduced populations in Michigan's northern Lower Peninsula, specifically in the Manistee National Forest and Pigeon River State Forest, have revealed that these groups have genetically diverged from their Ontario source populations and have experienced a loss of genetic diversity due to a genetic bottleneck.4 This reduced genetic variation is a serious concern, as it can diminish a population's evolutionary potential, increase its susceptibility to diseases, and elevate the likelihood of deleterious inbreeding and mutational meltdown.5

Habitat fragmentation continues to pose a substantial hurdle. While some previously fragmented forests in the Lower Peninsula have reconnected, forming more viable habitat, these areas often lack the characteristics of old-growth forests that martens prefer.4 Martens are also known to avoid large habitat openings, which expose them to aerial and land predators such as horned owls, eagles, and coyotes.4 Furthermore, reintroduction efforts have sometimes been constrained by external factors, as seen when public pressure from Ontario limited the number of martens that could be transferred to Michigan for Lower Peninsula reintroduction.3

The observation that reintroduction efforts have been deemed "successful" and martens are "re-established" in many U.P. habitats, while simultaneously facing severe genetic bottlenecks, loss of diversity, and associated risks, presents a complex situation. This creates a situation where, while demographically stable or increasing in numbers, the populations may be genetically fragile. This implies that "success" is a multi-faceted and ongoing challenge, not a singular achievement. The long-term persistence of these populations is at risk despite initial re-establishment.

3.4 Successes and Adaptations: Evidence of Population Recovery and Natural Dispersal

Despite the challenges, efforts to restore the American marten and fisher have shown demonstrable success throughout the Upper Peninsula.10 Biologists tracking martens have observed clear indications that the animals are readapting to their native Michigan habitats.2 Cody Norton, the MDNR furbearer specialist, has confirmed that martens are re-established in many prime habitats across the U.P..3 As a positive sign of their return, martens are increasingly encountered by outdoor recreationists, including hikers, campers, trappers, and hunters.2

Perhaps one of the most compelling indicators of recovery and adaptability is the recent discovery of American martens in the Apostle Islands of Wisconsin, an area adjacent to the U.P. Genetic research has revealed that this population naturally dispersed to the islands from a closely related population in upper Michigan, rather than being descendants of the failed Pacific marten reintroduction from the 1950s.9 This natural recolonization is believed to have occurred relatively recently, approximately 20 years ago.9 Martens are known for their ability to travel long distances, with individual ranges extending up to 50 miles, and they are thought to move between islands by crossing ice.11 This natural dispersal capability suggests that higher-density island populations could potentially serve as "source populations," contributing to the recolonization of mainland areas.9 These developments highlight the species' resilience and the efficacy of sustained conservation efforts in fostering recovery and range expansion.

4. Current Status and Management

4.1 Estimated Population Abundance and Distribution in the U.P.

The American marten is now re-established in numerous prime habitats within Michigan's Upper Peninsula.3 The Michigan DNR initiated the collection of marten population trend data when limited public trapping was permitted in 2000.3 During the period of 2000-2007, the estimated abundance for the U.P. ranged from approximately 1,200 to 1,700 martens.3 However, despite these re-establishment efforts, populations have not significantly grown or expanded their range since that time, and sightings or incidental catches by trappers remain rare.3 The distribution of martens, as inferred from harvest data, is generally concentrated in the northern half of the U.P..3 In contrast, in northern Wisconsin and the Lake Superior islands, which share ecological characteristics with the U.P., wildlife biologists estimate a much smaller population of only 30 to 80 animals, underscoring the continued rarity of the species in the broader region.11 Nevertheless, martens have naturally recolonized 11 of the 22 Apostle Islands, demonstrating their capacity for movement and potential to establish new populations, often by traveling across ice.9

4.2 Michigan DNR's Role in Monitoring and Management (including trapping seasons)

The Michigan Department of Natural Resources (MDNR), in collaboration with the U.S. Forest Service, plays a central role in the ongoing monitoring and management of American marten populations.2 Following successful restoration efforts, the first modern marten trapping season was initiated in 2000.10 In 2018, 6,016 furtakers obtained a harvest tag for either marten or fisher, with 637 specifically targeting martens.10 That same year, the maximum allowable harvest (bag limit) for martens was increased from one to two, while the season length was reduced from 15 to 10 days.10

Between 2017 and 2018, the number of registered martens significantly increased by 113%, rising from 186 to 396 individuals. Concurrently, the trapper effort required per registered marten decreased notably.10 This could suggest either an increase in marten numbers or improved trapping efficiency and distribution. However, the initiation of a new research project by the DNR to develop updated abundance estimates for martens 3 implicitly acknowledges that "successful restoration" might be relative, and careful monitoring is crucial to avoid a return to overharvesting. This situation highlights a delicate balance in "managed recovery" and sustainable harvest. While the increased harvest numbers and reduced effort per marten might suggest a robust population, the observation that populations have not significantly expanded or increased in sightings since 2007 raises questions about the true population dynamics. The DNR's new research project is a vital step in ensuring that management decisions are based on accurate population assessments, preventing potential over-exploitation of a still-fragile population.

Beyond direct population management, the DNR also influences marten habitat through its forest management practices. Michigan state forest timber management employs a modified area control method, which aims to balance age classes of trees to ensure sustained timber yields.12 These practices directly impact the availability and quality of marten habitat. Furthermore, DNR foresters actively develop Forest Stewardship Plans for private landowners, offering guidance on wildlife habitat and forestry goals, sometimes with financial assistance for resource management.13

4.3 Ongoing Research and Future Conservation Outlook

Current research initiatives are crucial for understanding and adapting marten conservation strategies. Projects include tracking martens with GPS collars to gain detailed information on their movements and prey selection.8 Comparative studies are underway to examine differences between marten populations in Michigan and Minnesota, focusing on diet and how martens utilize different forest types to find prey.8 The findings from this research are intended to inform habitat improvement decisions, particularly in areas like the Manistee National Forest in the Lower Peninsula.8

A significant focus of ongoing research is the impact of climate change. Martens are well-adapted to deep snow, which provides them with a competitive advantage over other predators like fishers and facilitates access to subnivean prey.1 A warming climate, characterized by reduced snowpack and shifts in prey communities, poses a substantial threat to these adaptations.1 Research aims to predict how martens will respond as prey communities change and if less snowpack will impact their survival and competitive edge.8 This focus on climate change implies that even with successful habitat restoration and regulated trapping, a new, pervasive, and less controllable threat could lead to a "second extirpation" or significant range contraction, fundamentally altering the long-term viability of the species in Michigan. Furthermore, for smaller, isolated populations, such as those naturally recolonizing the Apostle Islands, limited genetic flow from the mainland could lead to negative repercussions over time, emphasizing the need for continued monitoring of genetic health.9

4.4 The American Marten as an Indicator of Forest Health

The American marten's specific habitat requirements and sensitivity to environmental changes position it as a valuable indicator species. Martens are widely regarded as a sign of good forest health.4 Their presence in areas like the Manistee National Forest, for example, can suggest that the forest ecosystem is in a healthy condition.4 Beyond forest health, the marten is also considered an indicator of how a warming climate may affect other wildlife species.1 Its adaptations to snow and reliance on specific prey make it a bellwether for broader ecological shifts driven by climate change, making its ongoing monitoring critical for understanding wider environmental impacts.

5. The American Marten in Indigenous Lore and Culture of Michigan's Upper Peninsula

5.1 Overview of Major Indigenous Tribes in the U.P.

Michigan's Upper Peninsula has been the ancestral homeland of various Algonquian-speaking tribes for millennia, with evidence of their presence dating back as far as 8,500-7,000 BCE.7 These communities include the Ojibwe, Menominee, Odawa, Nocquet, and Potawatomi, who are collectively known as the Anishinaabe.6 The Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi share a particularly close historical bond, stemming from a common origin as one large tribe that is said to have split near the Straits of Mackinaw in the 16th century.14 These three nations formed a powerful long-term tribal alliance known as the "Council of Three Fires," which played a significant role in the region's history, including conflicts with the Iroquois Confederacy and Dakota people.14 Their oral histories and traditions are deeply rooted in the landscape of the Upper Peninsula, reflecting a profound and enduring connection to the land and its animal inhabitants.

5.2 The Anishinaabe Clan System and the Marten (Waabizheshi) Totem

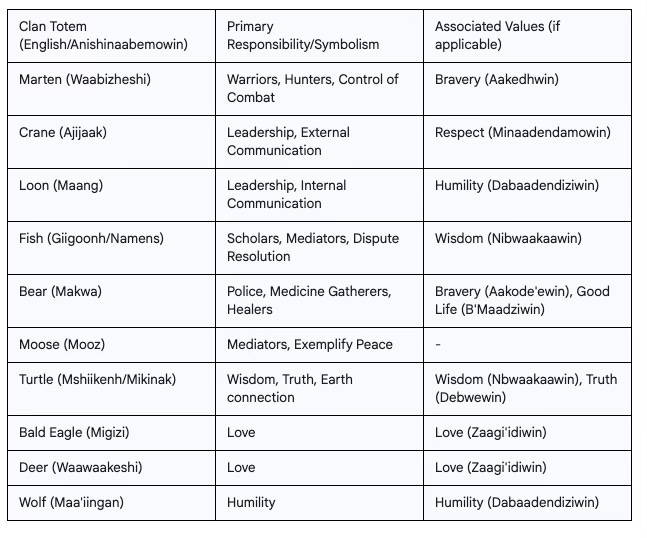

Central to the social and spiritual organization of the Anishinaabe peoples is their system of kinship based on clans, or doodeman, named predominantly after animal emblems.16 The term

doodem itself is profound, literally translating to "the expression of, or having to do with one's heart," signifying the extended family and the core identity of an individual.16 This clan system forms a foundational framework for society, with each totem representing a core branch of knowledge and responsibility essential to the community's well-being. A fundamental tenet of this system is that members of a clan are forbidden from harming their representation animal, as doing so is considered a bad omen.16

The Marten (Waabizheshi) is a particularly respected clan animal within the Anishinaabe system, holding significant symbolic meaning. It is revered for its exceptional hunting prowess, thus serving as one of the totem animals representing hunters.18 Historically, the Marten Clan held the crucial role of warriors among the Ojibwe, responsible for combat and protection.1 Fred Ackley, a member of the Marten Clan from the Sokoagon/Mole Lake Band, describes their ceremonial duty within the lodge as guarding the western door.18 Furthermore, the Marten clan is explicitly associated with the value of "Bravery" (

Aakedhwin) within the Anishinaabe Seven Grandfather Teachings, reinforcing its esteemed position.17 The marten's luxuriant fur pelt also holds ceremonial importance, being used as part of specific rituals within the Lodge.18 The marten is not merely an animal present in the environment but is deeply embedded in the Anishinaabe social, spiritual, and governance structures through the clan system. Its role as a warrior/hunter totem, its association with bravery, and its use in ceremonies elevate it beyond a typical wildlife species. This suggests that the marten functions as a "cultural keystone species"—its presence and health are intrinsically linked to the health and continuity of indigenous cultural practices, knowledge systems, and identity. Its extirpation would not just be an ecological loss but a profound cultural one.

Table 2: Anishinaabe Clan System: Core Totems and Responsibilities (Highlighting Marten)

Note: This table represents a selection of common Anishinaabe clans and their associated roles, with variations existing across different communities and traditions. The values listed are part of the Seven Grandfather Teachings, often linked to specific totems.

5.3 Specific Tribal Narratives and Stories Involving the Marten/Weasel Family

The cultural significance of the marten extends into specific tribal narratives, particularly within the Potawatomi oral tradition. One notable story recounts the tale of Pine Marten and his brother Weasel, who is cunningly stolen by Lizard.19 The narrative details Pine Marten's determined quest to rescue his brother, embarking on a perilous journey with the aid of powerful allies like Moon and Coyote, who even transforms into an old woman to deceive Lizard.19 The story is rich with themes of kinship, bravery, and overcoming adversity through wit and perseverance, culminating in Pine Marten's clever act of skinning Lizard and burning his house to free Weasel.19 This narrative not only entertains but also transmits important cultural values and lessons about family, courage, and strategic thinking.

More broadly, within the Anishinaabe tradition shared by the Odawa, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi, figures like Ne-naw-bo-zhoo (a prominent trickster and transformer) frequently appear in origin stories and teachings.15 Ne-naw-bo-zhoo possesses the ability to "transfigure himself into the shape of all animals" 20, highlighting a cultural context where animal forms are fluid and hold deep symbolic and instructional significance. Although not always explicitly featuring the marten, these narratives underscore a worldview where animals are not merely resources but sentient beings with agency, wisdom, and a role in shaping the world and teaching humanity.

5.4 Integration of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) in Understanding the Marten's Significance

The enduring cultural importance of the marten to the Ojibwe people is understood both historically and in contemporary contexts.1 This understanding is increasingly being recognized and integrated into modern conservation efforts. Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) of the Lake Superior Ojibwe people is actively combined with Scientific Ecological Knowledge (SEK) to assess the vulnerability of species like the marten to emerging threats, such as climate change.1 This collaborative approach demonstrates a dynamic application of traditional understanding in contemporary conservation challenges.

The Anishinaabe clan system itself serves as a sophisticated mechanism for acquiring and retaining knowledge, passed down through generations.16 This system embodies a deep, experiential understanding of the natural world, where knowledge gained through interactions with the environment and other clan members is continuously built upon and transmitted. The continued recounting of stories like that of Pine Marten and the active use of the clan system for knowledge retention illustrate the resilience of indigenous oral traditions and cultural frameworks. These knowledge systems are not static relics of the past but dynamic, adaptable frameworks that can inform and enrich modern conservation strategies, especially in the context of new threats like climate change, where TEK is explicitly being combined with SEK. This integration underscores the mutual benefits of such collaborations for both ecological health and cultural preservation.

6. Conclusion

6.1 Synthesis of Findings on the Marten's Ecological and Cultural Journey

The history of the American Marten in Michigan's Upper Peninsula is a compelling narrative of ecological struggle and enduring cultural significance. From its historical presence as a widespread native species across Michigan, the marten experienced a dramatic decline, culminating in its near extirpation by the 1930s. This ecological collapse was primarily driven by human activities: the extensive logging of old-growth forests, which destroyed its specialized habitat, and unregulated trapping that decimated its populations. The subsequent decades have seen arduous and dedicated reintroduction efforts by state and federal agencies, leading to the re-establishment of martens in many prime habitats within the U.P. However, this recovery remains precarious, with populations facing ongoing challenges such as genetic vulnerability due to bottlenecks and the emerging, pervasive threat of climate change.

Beyond its ecological trajectory, the American Marten holds a profound and enduring cultural significance for the indigenous Anishinaabe peoples of the region, including the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi. As the revered Waabizheshi (Marten) clan totem, it is deeply embedded in their social, spiritual, and governance structures. Symbolizing bravery and hunting prowess, the Marten Clan traditionally served as warriors and hunters, embodying core societal responsibilities and values. Its presence in oral traditions, such as the Potawatomi narrative of Pine Marten and Weasel, further underscores its integral role in transmitting cultural knowledge, values, and identity across generations. The marten's story in the U.P. is thus a powerful testament to the intricate and inseparable connection between the health of a species and the continuity of human culture.

6.2 Implications for Ongoing Conservation and Cultural Preservation

The journey of the American Marten in Michigan's Upper Peninsula carries significant implications for future conservation and cultural preservation efforts. While reintroduction programs have achieved a degree of demographic success, the ongoing challenges of genetic vulnerability and the increasing impact of climate change necessitate a shift towards more adaptive and holistic conservation strategies. Future efforts must extend beyond simply increasing numbers to focus on maintaining and enhancing landscape-level connectivity, facilitating genetic exchange, and building climate resilience within marten populations. This requires a nuanced understanding of how changing snowpack, prey communities, and habitat availability will affect the species' long-term viability.

Crucially, the history of the American Marten in the U.P. underscores the vital importance of recognizing and integrating Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) from indigenous communities into modern conservation practices. The Anishinaabe's deep, intergenerational understanding of the marten's ecology, behavior, and cultural significance offers invaluable perspectives that can inform and enrich contemporary scientific approaches. Collaborations that bridge TEK and Scientific Ecological Knowledge (SEK) are not only beneficial for the ecological health of species like the marten but are also essential for the preservation and revitalization of indigenous cultural practices and knowledge systems. Ultimately, the American Marten's story in Michigan's Upper Peninsula serves as a poignant reminder of human impact, the remarkable resilience of nature, and the profound interconnectedness of ecological well-being and cultural heritage.

Share this post